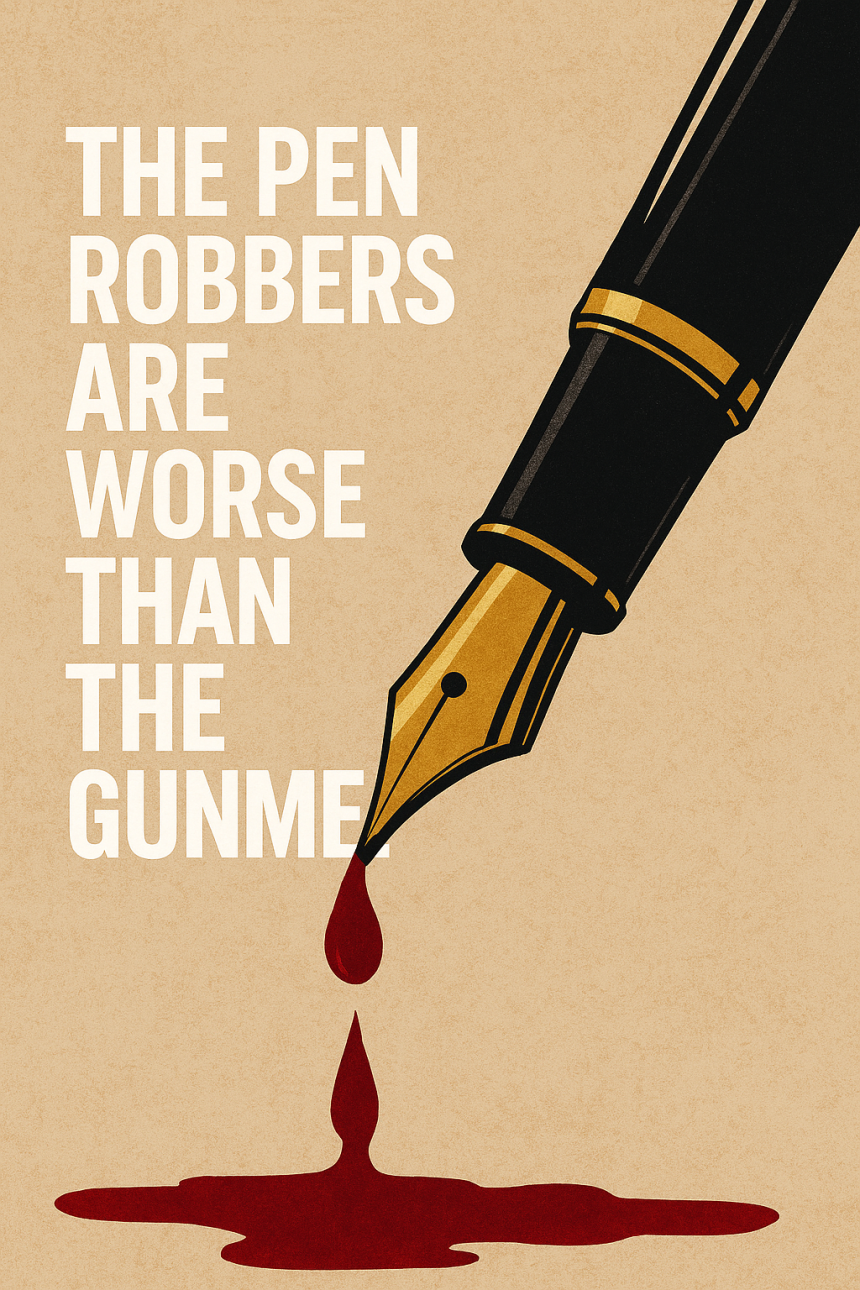

While gunmen terrorize highways and villages, a quieter but deadlier group operates behind office doors, wielding not weapons but pens. These are the “pen robbers” a phrase recently popularized by political analyst and publisher Dahiru Yusuf Yabo, who describes them as the architects of Nigeria’s invisible destruction.

In his viral essay titled “The Pen Robbers Are Worse Than the Gunmen,” Yabo argues that corruption committed with ink and signatures has crippled Nigeria more deeply than the violence of armed criminals. “The gunman may take your life,” he writes, “but the penman takes your destiny.”

From inflated contracts to falsified votes and padded budgets, Nigeria’s story of corruption often begins not with a gunshot, but a signature. Every misappropriated fund, delayed project, or looted budget passes through the stroke of a pen.

Public records show that Nigeria loses an estimated ₦18 trillion annually to corruption, according to reports by the Independent Corrupt Practices and Other Related Offences Commission (ICPC) and the Auditor-General’s office. Yet, many of these crimes are “technically legal” disguised under contract approvals, procurement waivers, or falsified reports that receive official endorsement.

“Corruption in Nigeria has evolved,” says an anti-graft analyst from the Centre for Transparency Advocacy. “It’s no longer the brown-envelope or bribe-by-hand kind of corruption. It’s bureaucratic written, approved, stamped and filed away as policy.”

Yabo’s argument captures a painful truth: the most dangerous thieves are not those hiding in forests but those occupying boardrooms and government offices. These are individuals whose decisions often signed into law determine who eats and who starves, who gets justice and who doesn’t.

Every inflated budget, every ghost worker, every uncompleted project is a quiet act of violence. It robs millions of Nigerians of schools, hospitals, and basic infrastructure. The gunman kills dozens, but the pen robber condemns generations.

Analysts believe this “administrative corruption” is at the root of insecurity. When public funds meant for jobs and development are siphoned off, unemployment and anger rise breeding the very conditions that sustain criminal networks.

“The bandits in the bush are often products of the biro thieves in Abuja,” Yabo wrote. “The biro thief is the root cause of the gunman’s rebellion.”

Nigeria’s bureaucracy is built on paperwork and that is both its strength and weakness. Documents are meant to ensure accountability, but they often become tools for concealment.

Procurement laws, though clear, are easily circumvented through “emergency clauses.” Budgets are padded with vague subheads like “special intervention” or “strategic support.” By the time auditors arrive, the trail is buried under multiple layers of approval.

Transparency groups like BudgIT and SERAP have repeatedly called for full digital publication of federal and state budgets in real time. Yet, only a few states notably Lagos, Kaduna, and Ekiti maintain open budget portals. Most others remain opaque, fueling speculation and corruption.

“The real crime is no longer stealing money directly,” says Dr. Mutiat Adeola, a public policy lecturer. “It’s designing a policy that allows money to disappear legally.”

The power of the pen extends beyond contracts. It shapes elections, determines justice, and dictates who holds power. Falsified electoral forms, doctored results, and conflicting court judgments have undermined public trust in Nigeria’s democracy.

“With the pen, elections are rigged and victory is stolen from the people,” Yabo noted in his article. “With the pen, godfathers decide who rules while citizens pretend to vote.”

The phrase resonates deeply at a time when the country grapples with disputed election results and judicial controversies. Many Nigerians now believe the true battle for democracy is no longer at polling stations but in courtrooms and offices where documents are signed.

Beyond politics, Yabo’s analogy extends to policy formulation. Every failed policy from fuel subsidy removals to unsustainable loans begins with a pen. The consequences are far-reaching: rising inflation, debt crises, and mass hardship.

“When a budget is inflated, a pen did it. When debt is piled up with no plan for repayment, a pen approved it,” Yabo wrote.

Economists argue that Nigeria’s growing debt, now above ₦121 trillion, is another example of “pen robbery.” Loans are contracted without transparent cost-benefit analyses, often for projects that never materialize.

Experts and reform advocates agree that fighting “pen robbers” requires more than arrests it demands systemic change.

First, the budget process must be fully transparent, with all contracts published online. Second, whistleblower protection must be enforced to encourage internal accountability. Finally, prosecutions for financial crimes must extend beyond junior officers to the architects of the schemes.

Yabo’s message, however, goes beyond institutional reform it is a call to moral awakening. “The gun may kill a man, but the pen kills a nation,” he warned. “Before you blame the gunmen, look for the biro thieves the silent architects of our misery.”

For him, Nigeria’s liberation begins not from the forests but from the offices. The revolution, he says, will not come from bullets but from ballots when citizens learn to reject biro thieves posing as reformers.

Yabo’s metaphor is not just a poetic outburst it is a diagnosis. Nigeria’s real war is not only against bandits and terrorists, but against bureaucratic banditry: the legalized, documented, and normalized theft of the nation’s future.

Until the “pen robbers” are treated as seriously as gunmen, the country will continue to bleed not from bullets, but from ink.