By Kabiru Abdulrauf

In just six weeks since the Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC) opened its online portal, more than 6.2 million Nigerians have pre-registered for their Permanent Voter Cards (PVCs). The numbers reflect a powerful statement: despite economic hardship, insecurity, and mistrust in institutions, Nigerians are still eager to vote. But the regional breakdown tells a more complicated story.

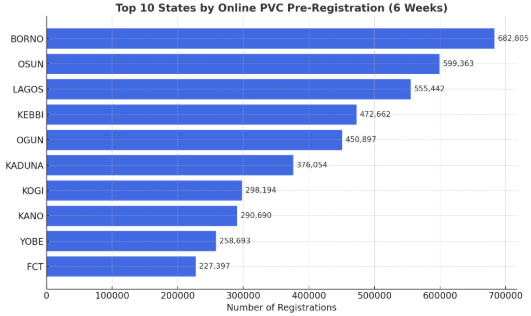

Northern states dominate the list, Borno leads with 682,805 registrations, followed by Osun (599,363), Lagos (555,442), Kebbi (472,662), and Ogun (450,897). In sharp contrast, some southern states recorded shockingly low numbers: Enugu (5,092), Abia (5,225), Ebonyi (6,935), and Edo (10,278). Even Rivers State, one of Nigeria’s economic engines, managed only 26,865 barely 4% of Borno’s tally.

The disparities highlight not just voter enthusiasm, but deeper social, political, and cultural dynamics shaping Nigeria’s democracy.

Borno – 682,805

Osun – 599,363

Lagos – 555,442

Kebbi – 472,662

Ogun – 450,897

Political mobilization in the North has historically been strong. Religious leaders, traditional rulers, and grassroots movements often drive voter registration as a communal duty rather than an individual choice. In states like Borno and Yobe, scarred by insurgency, participation is also framed as resistance proof that citizens refuse to be silenced by insecurity.

In contrast, parts of the South show signs of voter fatigue. Analysts point to apathy, migration, and mistrust in electoral institutions. Many young people relocate from rural to urban areas without updating their registration, while others express disillusionment with outcomes of past elections, believing their votes don’t matter.

Enugu – 5,092

Abia – 5,225

Ebonyi – 6,935

Edo – 10,278

Ondo – 14,388

These numbers are not just low they risk leaving millions of citizens without a voice in 2027.

Beyond the raw figures, INEC officials warn of a critical next step “completing biometric capture” at designated centres, without which online pre-registration means little. Already, past exercises have seen millions of registrations voided because citizens failed to follow through.

The surge also raises logistical questions. Can INEC handle both the sheer numbers and the security challenges that accompany voter registration in volatile regions? And will Nigeria’s political class respect the will of voters once expressed at the ballot box?

For now, the numbers offer a glimpse into Nigeria’s restless democracy a country where millions, despite hardship, are unwilling to surrender their right to vote.

With more students and young professionals registering online, 2027 could see one of Nigeria’s youngest electorates in history, Regional Influence in registration may tilt political negotiations, party primaries, and eventual election outcomes, Logistical failures or mass disenfranchisement could reignite mistrust in Nigeria’s electoral system.